Contact

Home

Nessie's Secret Revealed

Loch Ness Monster

Nessie’s Secret Revealed

by Tim Mendham

The Skeptic (Vol 14 No 2)

Page Number: 26-28

“I realised, for the first time, with complete assurance, the picture was not a fake and that the Loch Ness Monster was real and tangible; a living animal -or one that had been real and alive when the picture was taken in 1934.”

“Loch Ness Monster”, fourth edition, 1982, Routledge & Kegan Paul, p53

So the late Tim Dinsdale, a leading Nessie hunter who had taken the only seriously considered motion picture film of the monster in 1960, described a classic photograph of the infamous resident of the Scottish Loch - a photograph which was to be the real inspiration for his throwing himself fully into the pursuit of the monster, and a photograph now revealed to be a hoax.

The revelation of the hoax says more about the willingness of believers to force evidence to suit their own inclinations than it does about the existence of a large creature in the loch.

Background

The photo in question is the so-called “Surgeon’s Photograph”, supposedly taken by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Kenneth Wilson, MA, MB, ChBCamb, FRCS, a gynaecologist, who supposedly took the photo in early April, 1934. (If the good surgeon’s qualifications listed above seem superfluous to the story, they are, but that was how he was presented in Nicholas Witchell’s book, “The Loch Ness Story”, for reasons which will become obvious.)

The story goes that Colonel Wilson, joint-lessee of a wildfowl shoot close to neighbouring Inverness, was driving northwards past the loch early one morning with a friend.

Stopping for a break, they noticed a commotion on the loch surface about two or three hundred yards from the shore.

The friend said “My God, it’s the Monster”, and Wilson ran back to his car to retrieve a camera he had brought to take photos of birds. For the technically minded, the camera was a quarter-plate model with a telephoto lens (unstated focal length) using plates with “almost certain . . . a relatively slow orthochromatic fine grain emulsion” (Dinsdale’s claim, p56).

Having made four exposures over a two minute period, Wilson took the plates to Ogston’s, an Inverness chemist, where he gave them to Mr George Morrison for development.

Wilson asked for particular care to be taken, and Morrison replied “You haven’t got the Loch Ness Monster, have you?”.

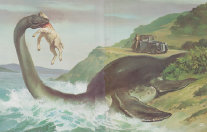

The plates were developed the same day. The first two were blank; the third, the most widely published, showed “an animal’s upraised head and neck”, with some associated bulk evident front and back and rippled water; and the fourth a very fuzzy depiction of the head and top of the neck disappearing beneath the waves.

On Morrison’s advice, Wilson sold the copyright of the third photo to the London Daily Mail which published it on April 21, 1934, “thereby challenging the evasive ingenuity of the scientific community yet again” (the ever- restrained Witchell, p45, 1975 edition, Penguin).

A further quote from Witchell is particularly ironic considering the recently revealed circumstances: “Colonel Wilson refused to enlarge upon the bare facts of his story and would not try to estimate the size of the object. In fact, he never claimed that he had photographed the ‘Monster’; all he ever said was that he had photographed an object moving in the waters of Loch Ness.”

Reaction

The publication of the photograph immediately created controversy, with believers claiming that it was absolute proof of Nessie’s existence (Nessie mania had in fact only been really up and running since the previous year) and sceptics calling it a hoax, some even suggesting it was taken in a London pond.

The Surgeon’s Photo, to be honest, is not very clear, showing a somewhat fuzzy “head and neck” in silhouette, with a partial reflection distorted by the disturbed water around the creature. It was normally published somewhat enlarged, showing less of the surrounding water than the now lost original plate. Nevertheless, Dinsdale, after studying the photo many times, from all angles, and holding the photo at arm’s length, felt that he could discern “a tiny knob or protrusion” on top of the head, complying with independent eye-witness accounts of horn-like stumps, and a second set of rippling circles somewhat behind the bulk of the monster, indicating disturbance caused by a further part of the animal. It was this moment of epiphany which gave rise to his conviction quoted at the head of this article.

Witchell described the photo as “believed to be the only genuine picture of the head and neck of one of the animals”, while admitting that it was nevertheless controversial.

The sceptics, on the other hand, dismissed the photo as an out-and-out hoax or, often, as the tail of an otter or a bird diving beneath the surface of the loch, or a tree trunk.

As to the photographer’s reticence for further comment, Witchell put this down to “professional reasons”: “The detached and entirely objective approach of Colonel Wilson is surely commendable. He made no wild claims and, as one would expect from a professional scientific man of standing [thus the long list of initials after his name], he merely reported what had happened as far as his recollection would allow him. Having done that he wished to have no part in the wrangling which inevitably follows every photograph purporting to show one of the animals.” Note the “purporting to show one of the animals”, rather than “one of the purported animals”.

Perhaps, there were other than “professional” reasons for the Colonel’s silence.

“I realised, for the first time, with complete assurance, the picture was not a fake and that the Loch Ness Monster was real and tangible; a living animal -or one that had been real and alive when the picture was taken in 1934.”

- “Loch Ness Monster”, fourth edition, 1982, Routledge & Kegan Paul, p53

So the late Tim Dinsdale, a leading Nessie hunter who had taken the only seriously considered motion picture film of the monster in 1960, described a classic photograph of the infamous resident of the Scottish Loch - a photograph which was to be the real inspiration for his throwing himself fully into the pursuit of the monster, and a photograph now revealed to be a hoax.

The revelation of the hoax says more about the willingness of believers to force evidence to suit their own inclinations than it does about the existence of a large creature in the loch.

Background

The photo in question is the so-called “Surgeon’s Photograph”, supposedly taken by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Kenneth Wilson, MA, MB, ChBCamb, FRCS, a gynaecologist, who supposedly took the photo in early April, 1934. (If the good surgeon’s qualifications listed above seem superfluous to the story, they are, but that was how he was presented in Nicholas Witchell’s book, “The Loch Ness Story”, for reasons which will become obvious.)

The story goes that Colonel Wilson, joint-lessee of a wildfowl shoot close to neighbouring Inverness, was driving northwards past the loch early one morning with a friend.

Stopping for a break, they noticed a commotion on the loch surface about two or three hundred yards from the shore.

The friend said “My God, it’s the Monster”, and Wilson ran back to his car to retrieve a camera he had brought to take photos of birds. For the technically minded, the camera was a quarter-plate model with a telephoto lens (unstated focal length) using plates with “almost certain . . . a relatively slow orthochromatic fine grain emulsion” (Dinsdale’s claim, p56).

Having made four exposures over a two minute period, Wilson took the plates to Ogston’s, an Inverness chemist, where he gave them to Mr George Morrison for development.

Wilson asked for particular care to be taken, and Morrison replied “You haven’t got the Loch Ness Monster, have you?”.

The plates were developed the same day. The first two were blank; the third, the most widely published, showed “an animal’s upraised head and neck”, with some associated bulk evident front and back and rippled water; and the fourth a very fuzzy depiction of the head and top of the neck disappearing beneath the waves.

On Morrison’s advice, Wilson sold the copyright of the third photo to the London Daily Mail which published it on April 21, 1934, “thereby challenging the evasive ingenuity of the scientific community yet again” (the ever- restrained Witchell, p45, 1975 edition, Penguin).

A further quote from Witchell is particularly ironic considering the recently revealed circumstances: “Colonel Wilson refused to enlarge upon the bare facts of his story and would not try to estimate the size of the object. In fact, he never claimed that he had photographed the ‘Monster’; all he ever said was that he had photographed an object moving in the waters of Loch Ness.”

Reaction

The publication of the photograph immediately created controversy, with believers claiming that it was absolute proof of Nessie’s existence (Nessie mania had in fact only been really up and running since the previous year) and sceptics calling it a hoax, some even suggesting it was taken in a London pond.

The Surgeon’s Photo, to be honest, is not very clear, showing a somewhat fuzzy “head and neck” in silhouette, with a partial reflection distorted by the disturbed water around the creature. It was normally published somewhat enlarged, showing less of the surrounding water than the now lost original plate. Nevertheless, Dinsdale, after studying the photo many times, from all angles, and holding the photo at arm’s length, felt that he could discern “a tiny knob or protrusion” on top of the head, complying with independent eye-witness accounts of horn-like stumps, and a second set of rippling circles somewhat behind the bulk of the monster, indicating disturbance caused by a further part of the animal. It was this moment of epiphany which gave rise to his conviction quoted at the head of this article.

Witchell described the photo as “believed to be the only genuine picture of the head and neck of one of the animals”, while admitting that it was nevertheless controversial.

The sceptics, on the other hand, dismissed the photo as an out-and-out hoax or, often, as the tail of an otter or a bird diving beneath the surface of the loch, or a tree trunk.

As to the photographer’s reticence for further comment, Witchell put this down to “professional reasons”: “The detached and entirely objective approach of Colonel Wilson is surely commendable. He made no wild claims and, as one would expect from a professional scientific man of standing [thus the long list of initials after his name], he merely reported what had happened as far as his recollection would allow him. Having done that he wished to have no part in the wrangling which inevitably follows every photograph purporting to show one of the animals.” Note the “purporting to show one of the animals”, rather than “one of the purported animals”.

Perhaps, there were other than “professional” reasons for the Colonel’s silence.

Revealed Hoax

On March 13 of this year, the London Sunday Telegraph published a story which claimed that the last of several men involved in hoaxing the photograph had made a confession before he died last November, to David Martin, a former zoologist with the Loch Ness and Morar scientific project, and fellow researcher Alastair Boyd.

According to the story and Christian Spurling’s confession, the Daily Mail had hired Marmaduke Wetherell, a film-maker, “big game hunter” and Mr Spurling’s stepfather, to find the monster. Wetherell asked Spurling to make him a monster, which he did using “plastic wood” attached to a 35cm toy tin submarine “bought for a few shillings from Woolworth’s in the London suburb of Richmond”.

According to one report (Sydney Telegraph Mirror 14/4/94), “a detailed study by . . . David Martin has found that Nessie was made in just eight days. The finished monster was 30cm high and about 45cm long with a lead keel to give extra stability.”

Wetherell’s son Ian took the photo on a quiet day on the loch. (Australian 14/4/94, Reuters report). A friend recommended Colonel Wilson as a front man, no doubt because of his impeccable scientific credentials and “commendable” detachment.

Admittedly, the two reports published in Australian newspapers and quoted above diverge somewhat. There is some slight difference on the number of people involved, with one report quoting five conspirators (Wetherell, son, stepson, Wilson and ?) and another a vaguer “several men”.

The Telegraph-Mirror says the photo was sold to an “unsuspecting newspaper”, whereas the Australian/Reuters report implies the newspaper was at least indirectly involved in the hoax. On this latter point, according to Witchell (pp39-41), in 1933 the Daily Mail had hired “a famous big-game hunter”, Mr M. A. Wetherall [sic], a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and Royal Zoological Society, to track down Nessie. After only four days Wetherall’s team came across footprints on the south shore of the loch. Plaster casts were made and sent off to the British Museum of Natural History, which early the next year reported that they were “unable to find any significant difference between these impressions and those made by a hippopotamus”. The footprints, it turned out, were made using a Loch Ness resident’s hippo foot umbrella stand, which probably explains why all the footprints were of the same foot!

Wetherall, on January 15, reported seeing something while cruising the loch, but he said he was convinced the loch only contained a large grey seal. The following year he resigned his Fellowship of the Royal Geographical Society. No more was heard of him, until the recent report.

Witchell makes no suspect (or otherwise) connection between the Daily Mail’s sponsoring of Wetherall/Wetherell, its apparently innocent publishing of his 1933 claims, and the same paper’s later publication of the surgeon’s photo.

He also, along with almost everyone else, apparently failed to notice what Ronald Binns, author of “The Loch Ness Mystery Solved” (Rigby, 1983), finds extremely significant, ie the date on which the photo was taken:

“When was that? ‘April of 1934’ says Tim Dinsdale; ‘early in one morning in April 1934’ adds FW Holiday in “The Great Orm of Loch Ness”; ‘early April’ agrees Witchell; ‘April 1934’ says Costello in “In Search of Lake Monsters”.”

Although clearly identified in Gould’s “Loch Ness Monster and Others” (1934) the date was not mentioned again until forty years later, in Professor Mackal’s “The Monsters of Loch Ness”: April 1st, 1934.”

April Fool’s Day joke or not, apparently the perpetrators of the hoax were “overwhelmed by the huge fuss their trick aroused and were afraid to confess”, a reaction shared by many another hoaxer. Nonetheless, their photo remained in active circulation for another 60 years, becoming the most famous photograph on the subject and reprinted almost without fail with every subsequent report or book.

Conclusion

The history of the surgeon’s photo is a classic cautionary tale for all involved in the search for proof of the paranormal, be it unknown animals, UFOs, psychic powers or whatever, and a particular warning for the use of photographic evidence.

Proponents of the surgeon’s photo stressed the supposed photographer’s impeccable scientific credentials and demeanour. Their attitude amounts to nothing less than ironic, naive and probably hypocritical snobbery, especially when one considers Witchell’s comment about the “evasive ingenuity of the scientific community”. Either they’re “detached” or they’re “evasive”, but they can’t be both.

They also stressed that the photo had not been tampered with, indicating that they are in dire need of a little application of Occam’s Razor, for they seemed to too rapidly overrule the possibility that it could be a real photo of a fake monster.

Dinsdale, in particular, was clearly prone to wishful thinking, claiming to see “a knob” on the top of the creatures head. Such detail is extremely indistinct in the photo, if not totally nonexistent. “It seems that these marks [the knob and the extra set of ripples] are either part of a very subtle fake, or genuinely part of the Monster, ” he said. The answer is they are neither, for it is not a photo of a genuine monster, and it isn’t a very subtle fake - the subtle aspects are in his mind.

The ripples circling out from the monster seem inordinately big, even for such a large and bulky creature as Nessie is often described to be. This in fact is the view of current (legitimate) investigators of the loch’s natural history, who claimed after the hoax’s exposure that for the last ten years no-one had given credence to the photo for this very reason.

The author of this article made this same point at an illustrated talk on unknown animals given at Sydney University in the mid-80s. But what seems obvious to some people is obviously invisible to others, particularly those with a predisposition to believe.

In the current age of computer-enhanced, computer-manipulated and more importantly computer-generated images, photographic evidence becomes entirely shaky. An original photograph can be scanned into a computer, enhanced to an almost infinite degree and a new, apparently untouched, negative produced.

Of course, there are still eye-witness reports to be dealt with, but these by their nature are intangible and prone to innocent and ingenuous enhancement of their own, as every friend of a fisherman will tell you.

In a way, it is sad to lose an icon of the age. The surgeon’s photo truly was a classic, not of the “real” Loch Ness Monster as it turns out, but perhaps of our wishful thinking for what we would like to think exists there. What it does represent, quite clearly, is how our wishes can run away with us, leading us to see what is not there, and to characterise our wishes as reality. In the future, as much as in the past, we would be advised to apply some common sense and commendable detachment before heading for the deep end of the loch.

Revealed Hoax

On March 13 of this year, the London Sunday Telegraph published a story which claimed that the last of several men involved in hoaxing the photograph had made a confession before he died last November, to David Martin, a former zoologist with the Loch Ness and Morar scientific project, and fellow researcher Alastair Boyd.

According to the story and Christian Spurling’s confession, the Daily Mail had hired Marmaduke Wetherell, a film-maker, “big game hunter” and Mr Spurling’s stepfather, to find the monster. Wetherell asked Spurling to make him a monster, which he did using “plastic wood” attached to a 35cm toy tin submarine “bought for a few shillings from Woolworth’s in the London suburb of Richmond”.

According to one report (Sydney Telegraph Mirror 14/4/94), “a detailed study by . . . David Martin has found that Nessie was made in just eight days. The finished monster was 30cm high and about 45cm long with a lead keel to give extra stability.”

Wetherell’s son Ian took the photo on a quiet day on the loch. (Australian 14/4/94, Reuters report). A friend recommended Colonel Wilson

as a front man, no doubt because of his impeccable scientific credentials and “commendable” detachment.

Admittedly, the two reports published in Australian newspapers and quoted above diverge somewhat. There is some slight difference on the number of people involved, with one report quoting five conspirators (Wetherell, son, stepson, Wilson and ?) and another a vaguer “several men”.

The Telegraph-Mirror says the photo was sold to an “unsuspecting newspaper”, whereas the Australian/Reuters report implies the newspaper was at least indirectly involved in the hoax. On this latter point, according to Witchell (pp39-41), in 1933 the Daily Mail had hired “a famous big-game hunter”, Mr M. A. Wetherall [sic], a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and Royal Zoological Society, to track down Nessie. After only four days Wetherall’s team came across footprints on the south shore of the loch. Plaster casts were made and sent off to the British Museum of Natural History, which early the next year reported that they were “unable to find any significant difference between these impressions and those made by a hippopotamus”. The footprints, it turned out, were made using a Loch Ness resident’s hippo foot umbrella stand, which probably explains why all the footprints were of the same foot!

Wetherall, on January 15, reported seeing something while cruising the loch, but he said he was convinced the loch only contained a large grey seal. The following year he resigned his Fellowship of the Royal Geographical Society. No more was heard of him, until the recent report.

Witchell makes no suspect (or otherwise) connection between the Daily Mail’s sponsoring of Wetherall/ Wetherell, its apparently innocent publishing of his 1933 claims, and the same paper’s later publication of the surgeon’s photo.

He also, along with almost everyone else, apparently failed to notice what Ronald Binns, author of “The Loch Ness Mystery Solved” (Rigby, 1983), finds extremely significant, ie the date on which the photo was taken:

“When was that? ‘April of 1934’ says Tim Dinsdale; ‘early in one morning in April 1934’ adds FW Holiday in “The Great Orm of Loch Ness”; ‘early April’ agrees Witchell; ‘April 1934’ says Costello in “In Search of Lake Monsters”.”

Although clearly identified in Gould’s “Loch Ness Monster and Others” (1934) the date was not mentioned again until forty years later, in Professor Mackal’s “The Monsters of Loch Ness”: April 1st, 1934.”

April Fool’s Day joke or not, apparently the perpetrators of the hoax were “overwhelmed by the huge fuss their trick aroused and were afraid to confess”, a reaction shared by many another hoaxer. Nonetheless, their photo remained in active circulation for another 60 years, becoming the most famous photograph on the subject and reprinted almost without fail with every subsequent report or book.

Conclusion

The history of the surgeon’s photo is a classic cautionary tale for all involved in the search for proof of the paranormal, be it unknown animals, UFOs, psychic powers or whatever, and a particular warning for the use of photographic evidence.

Proponents of the surgeon’s photo stressed the supposed photographer’s impeccable scientific credentials and demeanour. Their attitude amounts to nothing less than ironic, naive and probably hypocritical snobbery, especially when one considers Witchell’s comment about the “evasive ingenuity of the scientific community”. Either they’re “detached” or they’re “evasive”, but they can’t be both.

They also stressed that the photo had not been tampered with, indicating that they are in dire need of a little application of Occam’s Razor, for they seemed to too rapidly overrule the possibility that it could be a real photo of a fake monster.

Dinsdale, in particular, was clearly prone to wishful thinking, claiming to see “a knob” on the top of the creatures head. Such detail is extremely indistinct in the photo, if not totally nonexistent. “It seems that these marks [the knob and the extra set of ripples] are either part of a very subtle fake, or genuinely part of the Monster, ” he said. The answer is they are neither, for it is not a photo of a genuine monster, and it isn’t a very subtle fake - the subtle aspects are in his mind.

The ripples circling out from the monster seem inordinately big, even for such a large and bulky creature as Nessie is often described to be. This in fact is the view of current (legitimate) investigators of the loch’s natural history, who claimed after the hoax’s exposure that for the last ten years no-one had given credence to the photo for this very reason.

The author of this article made this same point at an illustrated talk on unknown animals given at Sydney University in the mid-80s. But what seems obvious to some people is obviously invisible to others, particularly those with a predisposition to believe.

In the current age of computer-enhanced, computer-manipulated and more importantly computer-generated images, photographic evidence becomes entirely shaky. An original photograph can be scanned into a computer, enhanced to an almost infinite degree and a new, apparently untouched, negative produced.

Of course, there are still eye-witness reports to be dealt with, but these by their nature are intangible and prone to innocent and ingenuous enhancement of their own, as every friend of a fisherman will tell you.

In a way, it is sad to lose an icon of the age. The surgeon’s photo truly was a classic, not of the “real” Loch Ness Monster as it turns out, but perhaps of our wishful thinking for what we would like to think exists there. What it does represent, quite clearly, is how our wishes can run away with us, leading us to see what is not there, and to characterise our wishes as reality. In the future, as much as in the past, we would be advised to apply some common sense and commendable detachment before heading for the deep end of the loch.

Return

Contents